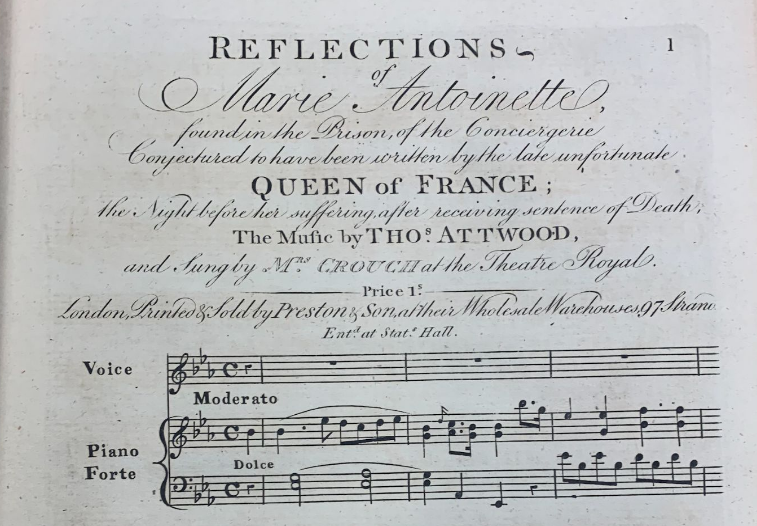

This week, my students gave fantastic presentations on rare items from the Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center at the Regenstein Library at UChicago. This is an assignment I’ve used for several years now in a core music history class I’m teaching for music majors in the college. Students choose which item they’ll present on, which is usually little-known, and the secondary sources on these items are often very limited. Each year I’m excited to put together the long list of items for students to choose from. This year, they included Thomas Attwood’s “Reflections of Marie Antoinette” (pictured), Emily Gilmore’s “President Garfield’s Funeral March,” and a manuscript of Giovanni Paisiello’s Socrate immaginario (The Imaginary Socrates), a comic opera about a man who reads so much ancient philosophy that he starts to think that he is Socrates.

These presentations answer the following questions:

- What are the physical materials of this item? What condition is this item in?

- What is the stylistic context of this item? Is your item a good representative of a particular genre? Is it exceptional?

- What does this music sound like? Can you find a 30-second clip of the music in your item, or music from a similar genre?

- What kinds of people may have been involved in using your item? Who originally wrote, printed, or bought this item? How was it used? How did it end up at the library?

This presentation helps show on how our conception of music history, which is often abstract and sometimes seems like a grand narrative of stylistic influence and progress, is in fact built upon actual artefacts used by real people. We can often see the “afterlives” of these artefacts in the way they end up in Special Collections: several items, for example, arrived here after they were acquired from the estate of Prof. Nicholas Temperley (d. 2020), an esteemed scholar of English music who taught at the University of Illinois, and some of the items were acquired under the direction of UChicago’s own Prof. Philip Gossett (d. 2017), a pathbreaking musicologist who specialized in Italian opera.

I think this assignment is an opportunity for students to see how thrilling archival research can be (honestly!). It’s tangible: you can touch these items and see the handwriting of the composers you’re studying. At the same time, it’s open-ended: in the absence of secondary literature, students learn to put together their own research questions and think about how their items were significant for musicians and listeners of the past. The most important thing about these presentations, to me, is to show how your research can carve out its own path, bringing new objects to light and building on musicological concepts that otherwise might seem to live only in the realm of the classroom. I’m always fired up to see what my students can make of these documentary sources, and I’m impressed by what my students accomplished. Congrats!